From 1945 to 1950: Music, rebirth and cultural reconstruction

The war was over! Bologna rediscovered its enthusiasm for living through music, dancing, meeting-rooms and the Filuzzi. The artists were the first interpreters of this wave of expressive freedom.

On 21st April 1945, Bologna was freed by the Allied Forces. The city had been sorely tried by the war and the bombings, but enthusiasm was fired by the end of the conflict and the fall of Fascism.

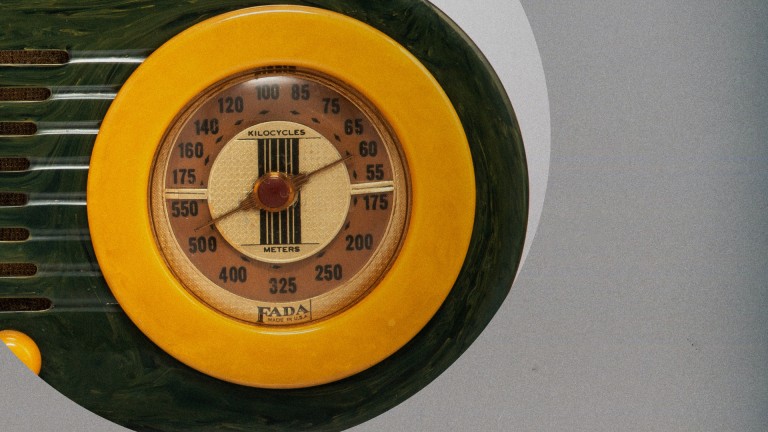

By late spring, there was a limited return to activity of some theatres and dance halls. Music discovered new energy, due above all to the influence of American culture, which had been prohibited during the regime. Fascism, in fact, has limited swing influence to a very few artists, such as the celebrated Alberto Rabagliati and the Trio Lescano.

Music related the traumatic experience, individual and collective, of the war.

Luciano Bonfiglioli, captured during the war and deported to a prison camp in the United States, was spotted for his gifts as a singer and inserted in a group that performed with the US Army. On returning to Italy, he began a new career. He appeared with several orchestras and in 1947 recorded the famous “Lettere d'amore”, from the soundtrack of William Dieterle’s 1945 film “Love Letters”.

Adriano Ungarelli, known as Adrianéin, was deported to Germany during the conflict but succeeded in escaping because he was believed dead in a collective execution. He is considered one of the most important Bolognese singers in dialect and was the principal interpreter of “Bela Bulåggna”, composed by Leonildo Marcheselli. Also celebrated was his interpretation of “El redder”, written by Carlo Musi, the most important writer of Bolognese songs in dialect.

Nilla Pizzi was a worker in the radio section of Ducati. She made her debut recording “Valzer di primavera” and “Ronda solitaria” for Parlophon in 1944, but achieved fame only in 1946 when she appeared with Cinico Angelini’s orchestra. Though contracted to Italian HMV, she also recorded for Cetra, Fon and Mayor using various pseudonyms. She became a diva in the 1950s with the birth of the Festival di Sanremo.

Renzo Angiolucci worked in Ducati together with Nilla Pizzi, with whom he occasionally performed. He joined the orchestra of Alda Scaglioni, a singing teacher in Bologna. Later, Gianni Morandi studied with Scaglioni and sung with her orchestra. Angiolucci’s career never achieved national fame, though his intense and productive activities won him the compliments of Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong.

Leonildo Marcheselli is considered the father of the Filuzzi, the artistic expression typical of Bologna that provided a new and original interpretation of the confluence between jazz, ballroom dancing, polkas, mazurkas and waltzes. Already active in the 1930s, Marcheselli changed his style, forming the “trio filuzziano”, consisting of the typical Bolognese organetto, guitar and double bass. This important evolution later expanded to a quartet.

The music of these years was dedicated to dancing, entertainment and socializing. It described the will to live and the desire for lightheartedness of the generation that had undergone the conflict.

Giorgio Consolini made his debut in 1947 with “Mandolinate a sera”, published with Teddy Reno’s CGD. It was an immediate success, enabling him to make more than twenty more recordings in the same year, including “Polvere e cenere”. Consolini later worked with the orchestras of Cinico Angelini and Armando Fragna, who dominated the Italian musical scene.

Many artists who were to write the history of music in Bologna were only just born: Francesco Guccini in 1940, Lucio Dalla in 1943 and Gianni Morandi in 1944, to mention only a few.

Over the following decades, music was increasingly to become a vehicle of social expression, giving shape to emotions, feelings, introspections, and diversity. It would break moulds, as its heterogeneous and conflictual evolution narrated life and sought to interpret it.

Listen to the playlist